Progressive Hypsometry and the glacial limitation of tropical mountain ranges

Application

Revealing glacial limitation of tropical mountain ranges

Absent glacial erosion, mountain range height is limited by the rate of bedrock river incision, and is thought to asymptote to a steady-state elevation as erosion and rock uplift rates converge. For glaciated mountains, there is evidence that range height is limited by glacial erosion rates, which vary cyclically with glaciations. The strongest evidence for glacial limitation is at mid-latitudes, where range-scale hypsometric maxima (modal elevations) lie within the bounds of late-Pleistocene snowline variation. In the tropics, where mountain glaciation is sparse, range elevation is generally considered to be fluvially limited and glacial limitation is discounted. Here we present topographic evidence to the contrary. By applying both old and new methods of hypsometric analysis to high mountains in the tropics, we show that (a) the majority are subject to glacial erosion linked to a perched base-level set by the snowline or equilibrium line altitude (ELA), and (b) many truncate through glacial erosion towards the cold-phase ELA. Evaluation of the hypsometric analyses at two field sites where glacial limitation is seemingly marginal reveals how glacio-fluvial processes act in tandem to accelerate erosion near the cold-phase ELA during warm phases and to reduce their preservation potential. We conclude that glacial erosion truncates high tropical mountains on a cyclic basis: zones of glacial erosion expand during cold periods, and contract during warm periods as fluvially-driven escarpments encroach and destroy evidence of glacial action. The inherent disequilibrium of this glacio-fluvial limitation complicates the concept of time-averaged erosional steady-state, making it meaningful only on long time-scales far exceeding the interval between major glaciations.

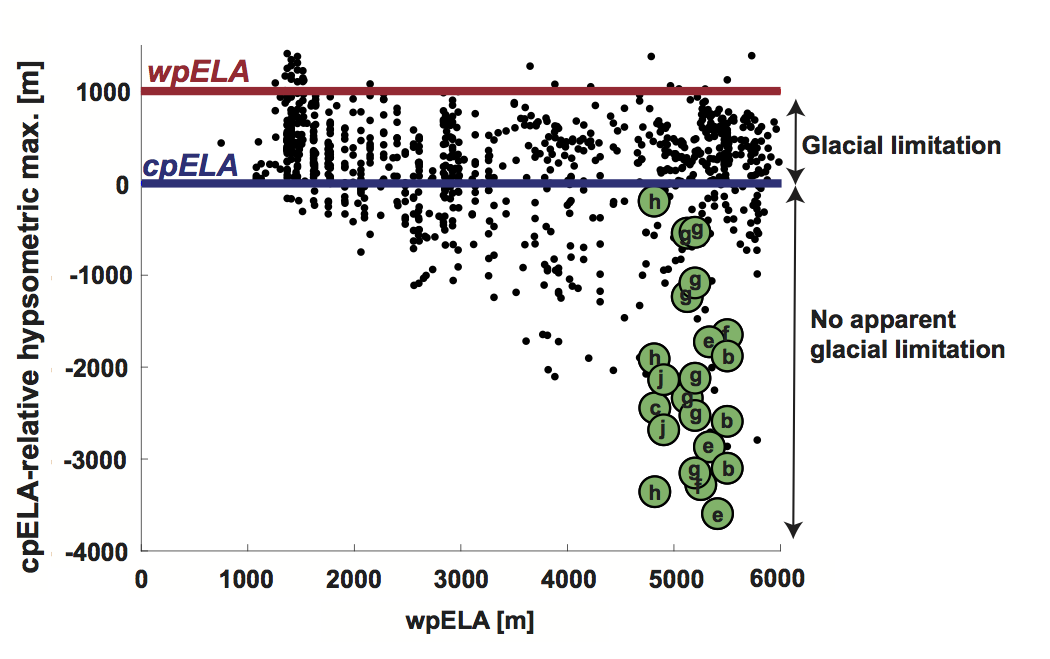

Hypsometric maximum of glaciated 1°x1° SRTM tiles (adapted from Fig. 2 of Egholm et al., 2009, data provided courtesy of V. Pedersen). Each tile is plotted by its approximate warm-phase (modern) ELA (wpELA; x-axis) and its hypsometric maximum relative to (after subtraction by) the cold-phase ELA (cpELA; y-axis); zero on the y-axis therefore indicates a hypsometric maximum at the cpELA. Glacial limitation is inferred for all SRTM tiles with a hypsometric maximum between the wpELA and cpELA. The tiles of tropical mountain ranges analyzed in this study are in green and labeled according to the scheme used in “Study sites”, Data, Analyses: (a) Leuser Range, Aceh (omitted here); (b) Central Range, Taiwan; (c) Talamanca Range, Costa Rica; (d) Crocker Range, Borneo (omitted here); (e) Finisterre Range, Papua New Guinea; (f) Owen Stanley Range, Papua New Guinea; (g) Merauke Range, Papua; (h) Mérida Range, Venezuela; (i) Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia (omitted here); (j) Rwenzori, East Africa. The Leuser Range, Crocker Range, and Santa Marta were not included in the analysis by Egholm et al., 2009.

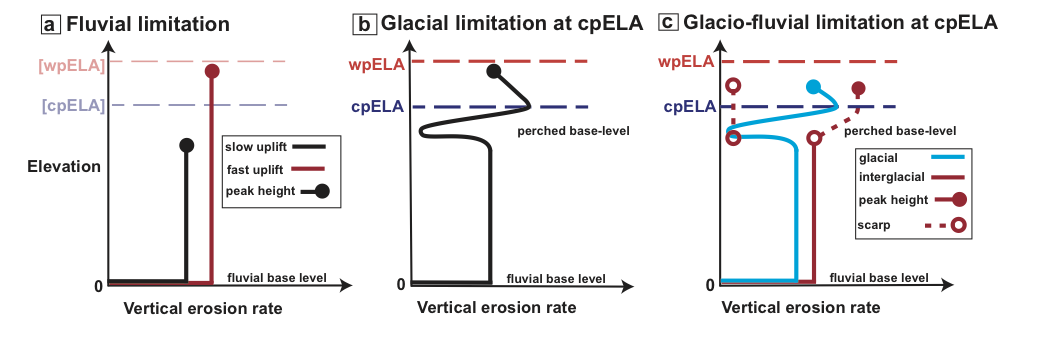

Fluvial limitation: vertical erosion rate vs. elevation in steady state, fluvially-limited regime. Black line: slow rock uplift; red line: fast rock uplift. The rate of rock uplift sets steady-state peak elevations (closed circle) at different elevations. Warm-phase ELA (wpELA) and cold-phase ELA (cpELA) are indicated for reference, but are irrelevant in this scenario. (b) Glacial limitation, with glacial base-level below the cpELA. Black line: erosion rate profile, with significant glacial influence at high elevations. Peak elevations reach above the cpELA, but are tied to glacial incision near this elevation. (c) Glacio-fluvial limitation. Blue line: erosion rate profile during glacial periods, similar to (b). Red line: interglacial erosion rate profile, characterized by headward migrating escarpment (along dashed line above erosion rate profile). During interglacials, erosion in previously glaciated landscapes is ineffective (dashed line, left hand side).